As a young seaman at the end of World War II, Owen Hardage had an unusual, if brief, encounter with an important personage. Here is Owen’s previously unpublished story, as ghostwritten by his wife Jeanette. (The story has been edited from the original for length).

The Emperor and I

I was a fire controlman on the USS Piedmont in August 1945. We had been at anchor for a month at Enewetak atoll in the South Pacific, in the northern Marshall Islands. Enewetak was being set up as a base for the planned invasion of Japan.

It was there we learned of Japan’s impending surrender. On August 15, a recording was played over the radio of the emperor reading his surrender announcement. This was the first time his subjects had heard his voice, this man they considered divine, a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu.

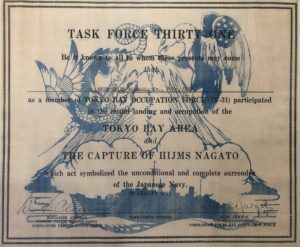

The USS Piedmont left Enewetak immediately for Japan, where she sailed off the coast for a few days. The ship proceeded to Tokyo Bay on August 29, finally anchoring at Yokosuka on August 30. When the surrender was signed aboard the USS Missouri on September 1, a few representatives were sent from each ship to observe the ceremonies.

The Piedmont remained at Yokosuka until February 1946. In September 1945, ship personnel were allowed to go ashore for recreation at Yokosuka Naval Station, formerly a Japanese base of operations. In October, restrictions were eased to allow liberty until dark. At this time, sailors began taking train trips to various cities on the main rail line. By the end of the year, liberty was extended until midnight.

Most sailors looked for silks, gems, or curios to purchase and send back home. Often they traded or brought gifts of items the Japanese were anxious to receive—soap, chocolate bars, cigarettes. Sailors sometimes rode up front with train engineers, who seemed glad of the company.

One clear, cold day in November, two buddies and I went sightseeing. Returning to Yokosuka, we had to change trains at Ofuna, a major junction point. After waiting on our platform along with Japanese passengers for some time that late afternoon, we began checking our watches and wondering what was keeping the train, as Japanese trains were always punctual. Soon we began hearing an announcement in Japanese, which we did not understand. The announcement was repeated again and again for a quarter of an hour. We noticed that other passengers had vacated our platform, and we were all alone.

Soon a train appeared, coming slowly into the station. It wasn’t the usual electric train, but one pulled by a coal-burning steam locomotive. The train did not stop, but slowly passed us by. In the middle of the train was a parlor car with a large picture window, and there, sitting in an easy chair, was His Imperial Majesty, Emperor Hirohito. He looked at us as he passed, and we recognized him at once. He looked exactly as he did in photographs I had seen. Then we looked behind us and saw several hundred Japanese people two platforms behind us, all bowing to their emperor. We later learned that the emperor was en route to Ise, making a ritual visit to report the outcome of the war to his ancestors.

When Hirohito became emperor of Japan in 1926, he named his reign Showa, or englightened peace. After the war, he renounced his divinity, but the Japanese people still revered him. The Showa reign lasted until Hirohito’s death in 1989.